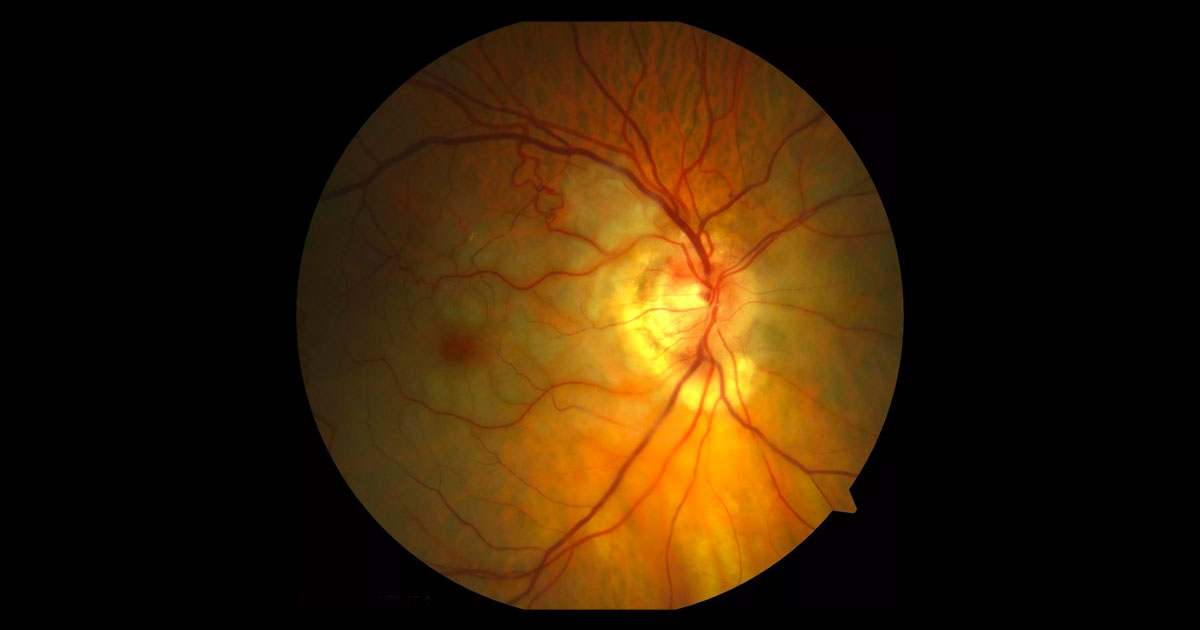

Figure 1. Colour fundus photograph shows pallor of the right retina with a cherry red spot at the macula.

A 76-year-old man was referred with acute painless visual loss in his right eye.

A 76-year-old male was referred by his general practitioner with acute painless vision loss in his right eye.

The patient reported having cataract surgery in both eyes 5 years ago but had no other ongoing ophthalmic complaints. Past medical included hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia treated with Coversyl® (perindopril) and Lipitor® (simvastatin) respectively.

Blood pressure was 158/ 94 mmHg and pulse was regular. Visual acuity was hand movements (HM) in the right eye (OD) and 6/6 in the left eye (OS). Prior to dilation a right relative afferent pupil defect (RAPD) was noted. The fundus examination demonstrated the right retina to be pale with a cherry red spot at the macula. An embolus was seen at the bifurcation of the inferior retinal arteriole (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Magnified view of the right optic disc shows an embolus at the bifurcation of the inferior retinal arteriole.

The most common causes of sudden profound vision loss are vascular and include:

- Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO)

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO)

- Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION)

- Vitreous Haemorrhage

The differential diagnosis for a cherry red spot includes:

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Metabolic storage disorders (e.g. Tay Sachs disease, Niemann Pick disease)

There were no symptoms of giant cell arteritis (GCA). Specifically the patient did not report jaw claudication, temporal and scalp tenderness, headache, neck stiffness or systemic malaise.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) through the right macula demonstrated hyperreflectivity within the inner retinal layers. This was not evident in the left macula on OCT (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Right and Left optical coherence tomography (horizontal raster scans) through the macula demonstrate high reflectivity localized to the inner retina in the right eye.

DIAGNOSIS

Right central retinal artery occlusion- (non arteritic).

A fluorescein angiogram was not performed as the diagnosis was clinical and angiography would not add further to the patient’s management. As the CRAO had been established for 24 hours, no ophthalmic treatment was recommended, as the retinal damage was irreversible.

After discussion with the patients’ general practitioner, aspirin was commenced and arrangements made for the patient to see a cardiologist. Electrocardiography (ECG) and cardiac echocardiography were normal. A carotid Doppler study, arranged to detect any carotid disease as the potential source of the embolus, demonstrated 70% stenosis on the right side and complete stenosis on the left. Subsequent consultation with a vascular surgeon recommended carotid endarterectomy. Vascular risk factors were checked.

Three weeks later visual acuity was still hand movements. The retinal pallor and cherry red spot had partially resolved, but the retinal embolus remained in the same positions. Disc pallor was developing and cilioretinal collaterals were evident (Figure 4). There was no iris or angle rubeosis.

Figure 4. Three weeks after initial presentation there has been resolution of the retinal pallor and cherry red spot. The retinal emboli is still present, and the optic nerve is becoming pale (compared with Figure 1). Cilioretinal collateral vessels are present at the disc.

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is analogous to a stroke of the eye. As a result of interruption to the arterial supply of the inner retina, patients present with severe unilateral painless visual loss. While the cherry red spot is the classical finding in CRAO, it is a consequence of retinal ischaemia and infarction and may not be present or easy to recognise within a few hours of the occlusion. Other important clinical findings in this early stage include a relative afferent pupillary defect, retinal arteriolar attenuation, segmentation of the arteriolar blood column (“cattle trucking”) and emboli. The OCT will demonstrate inner retinal hyperreflectivity, as in this patient, corresponding to oedema, remembering that the retinal vascular system supplies only the inner retina with the outer retina receiving its metabolic supply from the choroid. Fluorescein angiography will demonstrate delayed filling of the occluded retinal artery system but is usually not required.

Emboli are the most common cause of CRAO and most often arise from the carotid arteries.(1) Accordingly patients with CRAO need a “stroke work up” with their general practitioner and physician with special attention to diagnosing and treating carotid disease (carotid ultrasound), cardiac disease (ECG to exclude arrhythmias, cardiac echocardiography for valvular disease or a mural thrombus) and cardiovascular risk factor control (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, hyperglycaemia and smoking cessation).

This patient demonstrates a calcific embolus. These are typically large chalky-white plaques found near the optic optic disc with a high risk of obstruction, as in this case. They are associated with cardiac valves calcification and carotid artery plaques. Other retinal arteriolar emboli that may be seen include cholesterol emboli (“Hollenhorst plaques”) and fibrinoplatelet plaques. Cholesterol emboli are smaller thin brightly reflective yellow plaques that unless large do not cause complete occlusion of the artery and are therefore often asymptomatic. They usually arise from atheromatous plaques in the aortic and carotid system. Fibrinoplatelet plaques are duller, grey and elongated, running partially along the length of an arteriole.

Just under 5% of cases of CRAO are due to giant cell arteritis (GCA).(2) In patients in whom an embolus cannot be seen and/or who have symptoms of GCA further investigation is required as this diagnosis has serious implications for vision loss in the fellow eye and requires prompt steroid treatment.

The acute treatment of CRAO involves attempting to restore central retinal artery blood supply. After 4 to 6 hours with no retinal blood supply the retina is irreversibly damaged so prompt intervention is required.(1,3) Unfortunately most patients present after this window so interventions are unlikely to be helpful.(1,3) Interventions to distalise the embolus including digital massage, hyperventilation manoeuvres and intraocular pressure lowering (medication and anterior chamber paracentesis) have only been reported in observational studies and probably do not add much beyond the natural history of the condition.(1,3)

Thrombolysis, which is used to treat ischaemic stroke within the first hours of presentation, has also been investigated in CRAO.(1,3) Thrombolytic medication is aimed at dissolving the clot to allow reperfusion. It is injected either via a peripheral vein (intravenous) or directly into the carotid or ophthalmic artery via catheter (local arterial) by an interventional neuroradiologist. There is considerable controversy regarding the benefit and also potential significant safety consideration such as stroke.(1,3) In any case only a minority of patients will present within the window for this treatment to be considered.

Unfortunately, the visual prognosis for CRAO is poor with only 10% of patients reporting meaningful recovery of vision.(4) Patients still need to be observed for iris and angle neovascularisation which can occur in up to 1/3 patients.(5) The onset of neovascularisation in CRAO is often one to two months post occlusion as opposed to the traditional 90 days in central retinal vein occlusion. Treatment is with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) to prevent neovascular glaucoma and a painful blind eye. Patients also need ongoing follow up with their general practitioner and physician to control cardiovascular risk factors and prevent further vascular events such as heart attack and stroke.

TAKE HOME POINTS

- CRAO is analogous to a stroke in the eye.

- The typical presentation of CRAO is with acute painless vision loss.

- While most cases are embolic 5% will be associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA) and any patients with GCA symptoms should be considered for further investigations for GCA as the fellow eye is at risk.

- Retinal damage is irrecoverable after 4 to 6 hours so prompt referral is required in if intervention is to be attempted.

- A “stroke work up” to exclude carotid and cardiac disease and prevent further episodes is critical.

- Patients with CRAO may develop anterior segment neovascularisation and should be checked regularly for this in the first few months following diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- Varma DD, Cugati S, Lee AW, Chen CS. A review of central retinal artery occlusion: clinical presentation and management. Eye 2013; 27: 688–697.

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Central retinal artery occlusion: visual outcome. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 376–391.

- Biousse V. Thrombolysis for Acute Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Is it Time? Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 146: 631-634.

- Rumelt S, Dorenboim Y, Rehany U. Aggressive systematic treatment for central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 128: 733–738.

- Rudkin AK, Lee AW, Chen CS. Ocular neovascularisation following central retinal artery occlusion: prevalence and timing of onset. Eu J Ophthalmol 2010; 20: 1042–1046.

Tags: painless vision loss, central retinal vein occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion, anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy