The diagnosis of VKH can be a challenging, particularly with its varied presentation, at various clinical stages. The combination of neurological symptoms and bilateral exudative retinal detachments (subretinal fluid) should raise high suspicion for the acute uveitic stage of VKH.

Unlike our patient, VKH is most commonly seen in pigmented races, such as Asians, Hispanics, American Indians, and Asian Indians. It appears to be more common in Japan, where it accounts for 6.7% of all uveitis referrals. In the USA, it accounts for 1-4% of all uveitis clinic referrals. Most studies report women to be more affected than men, and most patients are 20-40 years of age.(1)

The primary pathology appears to be an autoimmune condition against melanocyte containing tissues such as uvea, ear, meninges and skin.(2) This explains the additional extraocular features of the disease, such as vitiligo, poliosis, tinnitus, vertigo and alopecia. Many of the skin findings are not found until the later stages of the disease.

In 2001, the First International Workshop on Vogt-Koyanagi Harada Disease revised the diagnostic criteria for VKH.(3) The criteria are as follows:

- No history of penetrating trauma or surgery

- No clinical or laboratory evidence suggestive of other ocular disease

- Bilateral ocular involvement (early disease: focal areas of subretinal fluid or bullous serous retinal detachments, choroidal thickening and fluorescein angiography changes such as multifocal areas of pinpoint leakage. Late disease: sunset glow fundus, retinal pigment epithelial clumping and migration)

- Neurological/auditory findings at any point during the course of the disease (eg. meningismus symptoms such as headache, fever, malaise, or stiff neck, tinnitus, or CSF fluid pleocytosis)

- Integumentary findings not preceding the onset of other central nervous system disease (eg. alopecia, vitiligo, poliosis)

Criteria 1-3 must be present for the diagnosis of probable VKH, all five criteria must be met for the diagnosis of complete VKH, and criteria 1-3 and either 4 or 5 must be met for the diagnosis of incomplete VKH. Our patient has a diagnosis of “incomplete VKH” as has he has not yet developed skin changes, but did have neurological symptoms when he presented (headaches, vertigo).

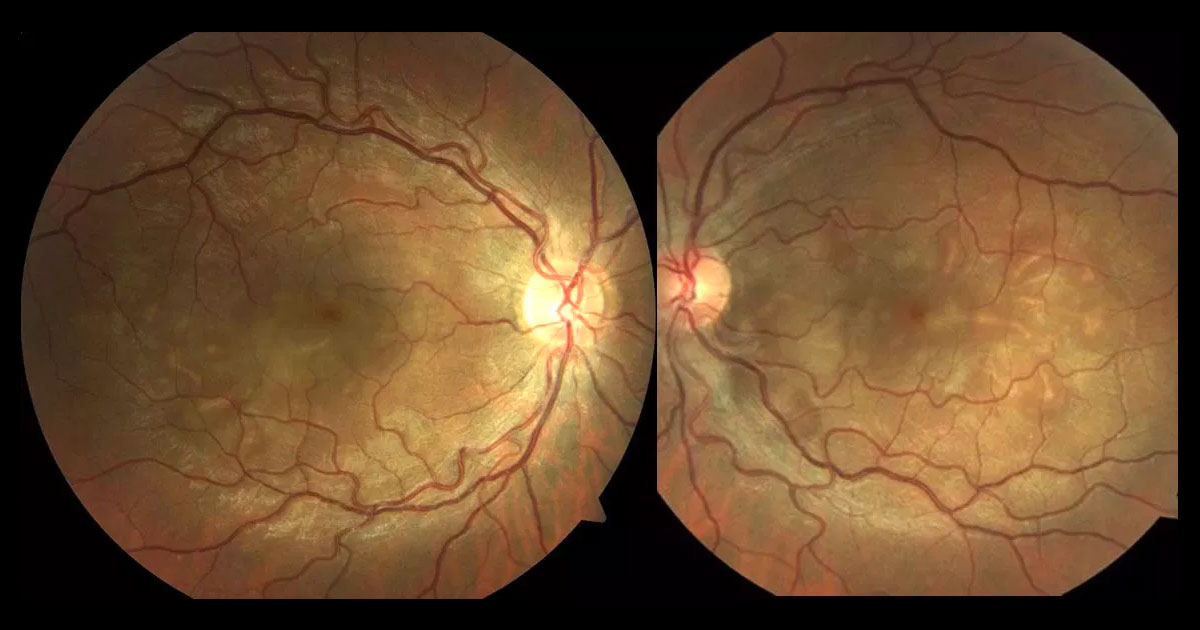

There are 4 stages to VKH. First is the prodromal stage, which may only last a few days, and can present similar to a viral-like illness. Headaches, nausea, dizziness, fever, neck stiffness and focal neurological signs can occur. The acute uveitic stage presents with a bilateral posterior uveitis, in the form of a multiple serous retinal detachments, and hyperaemia of the optic nerve heads. This is the stage our patient presented with. The OCT, FFA and ICG are all key investigations at this stage. The OCT shows pockets of subretinal fluid, often “tacked down” to the retinal pigment epithelium, presumably by fibrin.

(4) Pigment epithelial detachments are absent. In 40% of cases there are intraretinal cysts, which differs from most other causes of cystoid macular oedema by its predominance in the outer retina with preservation of the inner retina. Enhanced-depth imaging OCT will often show thickening of the choroid, which can be used to monitor disease activity. Fluorescein angiography typically shows pin-point hyperfluorescence in a “starry sky” appearance. The third stage is the chronic uveitic stage which is characterised by the development of vitiligo, poliosis and depigmentation of the choroid (“sunset-glow fundus”). The fourth stage is the chronic recurrent stage where episodes of granulomatous anterior uveitis occur, and vision-threatening complications such as subretinal neovascular membranes, glaucoma and cataract develop.

The differential diagnosis includes sympathetic ophthalmia, hence the need to exclude prior trauma or surgery. Central serous chorioretinopathy can present with serous retina detachments and a thickened choroid, but it may also have pigment epithelial detachments, the optic discs are not hyperemic and there are no systemic symptoms. It is important to exclude other infectious and inflammatory conditions.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease disease needs early, aggressive treatment with high dose corticosteroids to shorten disease duration and to reduce the risk of vision threatening complications and extraocular manifestations developing. Prednisone is normally started in 80-100mg orally (or 1-2mg/kg) with an individualised taper over a 6 month period.

(5) 60% of patients achieved better than 6/12 vision with this treatment regimen.5 Recurrences of the disease are not so steroid responsive, and may require other immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate, or cyclosporine.