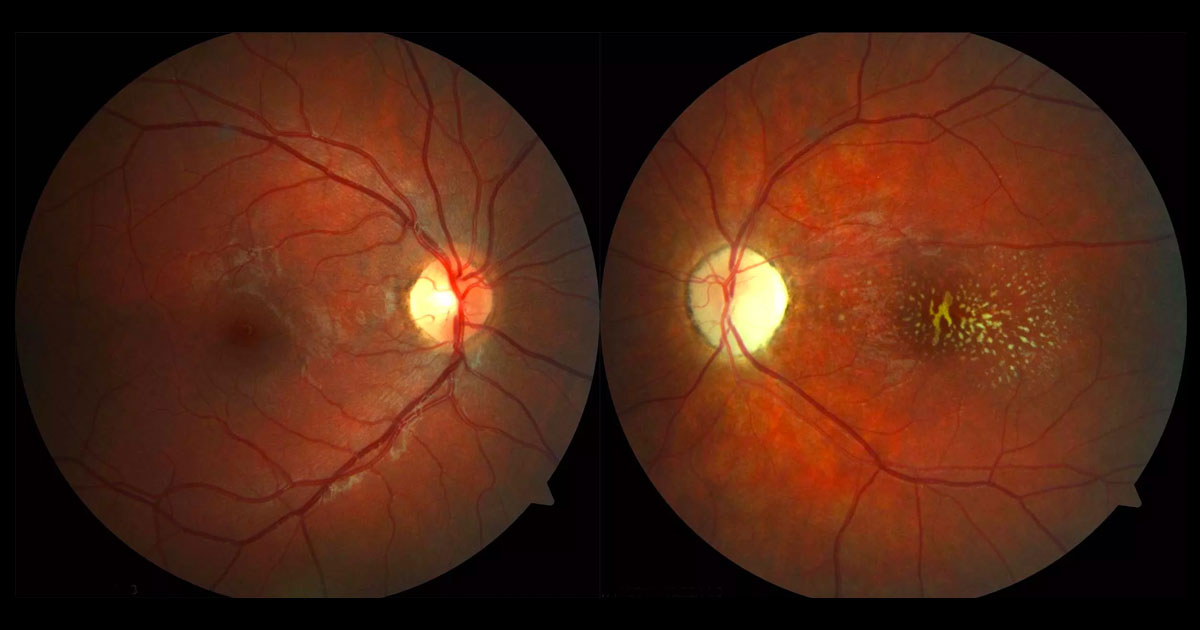

Neuroretinitis is characterised by papillitis and stellate macular exudates.(1) The most common cause of neuroretinitis is cat-scratch disease,(2-4) caused by the gram negative bacterium Bartonella henselae. The primary host reservoir for Bartonella henselae are cats, between which it is transmitted by Ctenocephalides felis, or the cat flea. The modes of transmission from cat to humans include: a cat-scratch by claws contaminated with cat flea faeces; or cat, cat flea, fly or tick biting.(3) Children and young adults appear to be more susceptible, with the greatest number of cases being reported in late autumn and early winter.(4) Following a cat scratch a pustule forms at the site of the scratch and is associated with regional lymphadenopathy and fever. About 5% of patients who suffer from cat scratch disease develop Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome (POGS): unilateral follicular conjunctivitis and preauricular, submandibular and cervical lymphadenopathy. Other ocular manifestations include:(4,5)

- Neuroretinitis (1-2% of cat scratch disease)

- Uveitis (anterior, intermediate, choroiditis)

- Retinal vasculitis and occclusions

- Inflammatory mass lesions(6)

The neuroretinitis is usually unilateral but bilateral cases have been reported.

(7) In the acute stages there is disc swelling (papillitis) with peripapillary subretinal fluid and macular oedema. Retinal haemorrhages and cotton wool spots may be present. The hard exudate deposition that forms a macular star is often delayed or may even never occur.

(2,4) Rarely, Bartonella henselae can affect the liver, spleen, heart (endocarditis), brain (meningitis, encephalitis), haematological system (anaemia), kidneys (glomerulonephritis) and bones (osteomyelitis, arthritis).

Diagnosis can usually be made by the clinical presentation in conjunction with positive IgG and IgM serology whilst excluding other causes. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used in cases with inconclusive serology.

(8) There is no consensus as to the best treatment for neuroretinitis secondary to Bartonella henselae.

(4) Various antibiotics have been used, including: fluoroquinolones (eg. ciprofloxacin), tetracyclines (eg. doxycycline), macrolides (eg. clarithromycin, azithromycin), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and rifampin. Systemic steroids have also been prescribed. Although the visual prognosis following neuroretinitis secondary to Bartonella henselae is often favourable

(2), visual deficits, such as in this patient, may be permanent. Re-infection is rare due to the development of immunity.

(4)