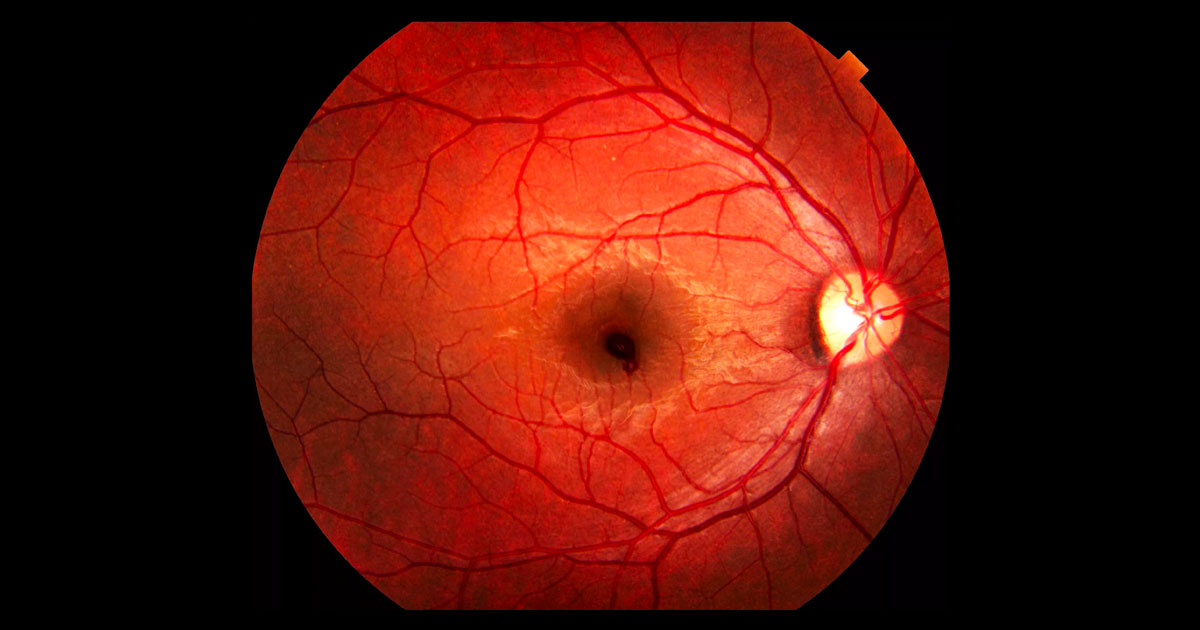

Figure 1. Right fundus photograph showing a haemorrhage at the right macula.

A 22-year-old man presented with a “blob” in the centre of his right vision.

A 22-year-old male electrical engineering student was referred by his optometrist after complaining of the sudden development of a “blob” in his right central vision.

The patient was a mild myope. At the previous examination with his optometrist his glasses had been strengthened to -1.25DS (right eye) and -1.00/ -0.50 x 88° (left eye). No other abnormality had been noted at that assessment. He had a past medical history of mild asthma and infrequently used a Ventolin® (salbutamol) puffer. He was not taking any anticoagulants or herbal medication.

Visual acuity was 6/18 in the right eye (OD) and 6/6+ in the left eye (OS). Fundus examination demonstrated a haemorrhage at the right macula (Figure 1). The haemorrhage was inner/pre-retinal, well demarcated and had an elevated appearance with a smooth dome shaped surface. There were no other haemorrhages in either eye. The retinal vasculature was otherwise normal with no arteriovenous nipping or reflex changes. There were no microaneurysms and no other vascular lesions noted. There was no posterior vitreous detachment visible in either eye. Optic nerves were healthy and intraocular pressures were 17mmHg in both eyes.

The differential diagnosis for an inner/pre-retinal haemorrhage at the macula in a young patient includes:

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Hypertensive retinopathy

- Haematologic disorders including

- Anaemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Leukaemia

- Valsalva retinopathy

- Terson’s syndrome

Blood pressure as measured in the rooms was 118/70mm Hg. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans through the fovea demonstrated the haemorrhage to be located in the inner retina and under the internal limiting membrane (sub ILM, Figure 2).

Fundus autofluorescence imaging demonstrated hypoautofluorecence in the location of the haemorrhage, confirming its location anterior to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) (Figure 3). This contrasts with sub-RPE haemorrhage, which does not block normal RPE hyperautofluorescence.

Full blood count looking for haematological disorders was normal with no anaemia, thrombocytopenia or leukaemia. Fasting blood glucose was also normal. Haemoglobin electrophoresis was not performed due to the patient’s demographic and the unlikeliness of him having sickle cell disease.

On further questioning the patient revealed that his disturbed vision had occurred after performing a shoulder press at the gym.

Figure 2. Right macular optical coherence tomography scan demonstrating the hyper-reflective haemorrhage located in the inner retina and underneath the internal limiting membrane (sub ILM).

Figure 3. Right fundus autofluorescence imaging demonstrating hypoautofluorecence in the location of the haemorrhage, due to blocking of normal retinal pigment epithelial hyperautofluorescence.

DIAGNOSIS

Valsalva retinopathy.

The diagnosis was explained to the patient and he was advised to avoid straining or other situations which might lead to a Valsalva manoeuvre. At review 4 weeks later vision had improved to 6/6- OD. The clinical examination demonstrated almost complete resolution of the sub ILM haemorrhage (Figure 4). No underlying vascular lesions were identified. The OCT demonstrated a small amount of residual inner retinal hyper-reflectivity (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Right colour fundus images four weeks after initial presentation. The macular haemorrhage has almost completely resolved.

Figure 5. Right OCT scan four weeks after intital presentation shows only a small amount of residual inner retinal hyper-reflectivity.

Valsalva retinopathy classically presents as painless central vision loss due to a macular haemorrhage following a Valsalva manoeuvre. A sudden rise in intrathoracic or intra-abdominal pressure, particularly against a closed glottis (Valsalva’s manoeuver), can cause a rapid rise in intravenous pressure within the eye and spontaneous rupture of superficial retinal capillaries.(1) Common causes of Valsalva include lifting, straining, bowel movements, coughing, vomiting and physical activity.

While most patients who develop the condition are healthy, underlying acquired retinal vascular abnormalities, such as diabetic or hypertensive retinopathy, retinal telangiectasis and congenital retinal artery tortuosity may increase the risk.(1)

The haemorrhages associated with Valsalva retinopathy are usually inner and pre-retinal and sharply demarcated, located at the posterior pole. They have a dome shape and there can often be overlying glistening from the internal limiting membrane. They may also extend into the vitreous and have sub and intra-retinal components.(1) The perifoveal capillaries are fragile, resulting in a predilection for the haemorrhage to occur at the macula.(1)

It is important to exclude haematological disorders as an alternative cause for inner and preretinal macular haemorrhages.(2) This includes anaemia, thrombocytopenia, leukaemia (Figure 6), and sickle cell disease.(2) Diabetic and hypertensive retinopathy are also important diagnostic exclusions.

The prognosis for spontaneous recovery is usually very good following Valsalva retinopathy.(1,2) In some cases the haemorrhage can be very large and would take a long time to resolve spontaneously (Figure 7). In these cases Nd:YAG laser may be used to puncture the posterior hyaloid allowing blood to escape into the vitreous cavity and eventually inferiorly away from the visual axis.(3) The laser should be performed within 3 weeks of onset as the haemorrhage will start to clot resulting in poor results as it cannot diffuse into the vitreous.(3) The procedure carries risks of retinal detachment, macular hole and epiretinal membrane formation.(2) Vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling has also been described with good success in the minority of cases that require intervention.(2) It carries with it the risks of intraocular surgery and acceleration of cataract formation that routinely follow vitrectomy.

Figure 6. A patient with leukaemia and multiple superficial and preretinal haemorrhages.

Figure 7. An extremely large left premacular haemorrhage due to a Valsalva manoeuver.

TAKE HOME POINTS

- Valsalva retinopathy typically presents with sudden visual loss in an otherwise healthy individual, caused by a premacular haemorrhage following a Valsalva manoeuvre.

- Common Valsalva manoeuvers include: lifting, physical activity, straining, coughing and vomiting.

- The haemorrhage in Valsalva retinopathy is usually welI demarcated and dome shaped, located within the posterior pole.

- Differential diagnoses include haematological disorders, hypertensive retinopathy and diabetic retinopathy.

- The haemorrhage usually resolves spontaneously with recovery of vision.

- Large and/or persisting haemorrhages may require intervention with Nd:YAG laser or vitrectomy with ILM peeling.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal A. Gass’ Atlas of Macular Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011

- De Maeyer K, Van Ginderdeuren R, Postelmans L et al. Sub-inner limiting membrane haemorrhage: causes and treatment with vitrectomy Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:869-872

- Durukan AH, Kerimoglu H, Erdurman C, et al. Long-term results of Nd:YAG laser treatment for premacular subhyaloid haemorrhage owing to Valsalva retinopathy. Eye 008 Feb;22: 214-8.

Tags: preretinal haemorrhage, diabetic retinopathy, valsalva retinopathy