Pseudophakic cystoid macular oedema, also known as Irvine-Gass syndrome, is one of the most common causes of reduced vision following cataract surgery. Peak incidence is at 4-6 weeks post-operatively(1). With modern small incision surgery, it has been reported to occur in up to 2% of cases(1), although OCT evidence of oedema that is not clinically significant may be detected in a much higher percentage of cases.

Whilst the pathophysiology is not completely understood, the upregulation of various inflammatory cytokines following surgery is believed to lead to an increase in vascular permeability in the macular capillaries, with subsequent accumulation of fluid(2).

Factors that are pro-inflammatory, such as intraoperative vitreous loss or iris trauma, or a previous history of uveitis, are known to increase the risk for this complication occurring(2). Diabetic retinopathy, and in particular a previous history of diabetic macular oedema, is also a known risk factor, due to the effect this condition has on endothelial permeability in the macular blood vessels (3). For this reason, in patients with previous macular oedema it is generally best to allow at least 3 to 6 months of documented macular stability before proceeding with planned cataract surgery.

The most common presenting symptom is reduced vision, and occasionally distortion, following recent cataract surgery. OCT demonstrates cystoid oedema and fluorescein angiography demonstrates a petalloid pattern of leakage, often with late disc staining (Irvine Gass syndrome).

The majority of clinically significant cases will resolve with topical steroid and non-steroid anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drops (4). These are usually used in a frequency of 4 to 6 times per day for several months. Some surgeons routinely use these drops pre-operatively to reduce the risk of macular oedema occurring.

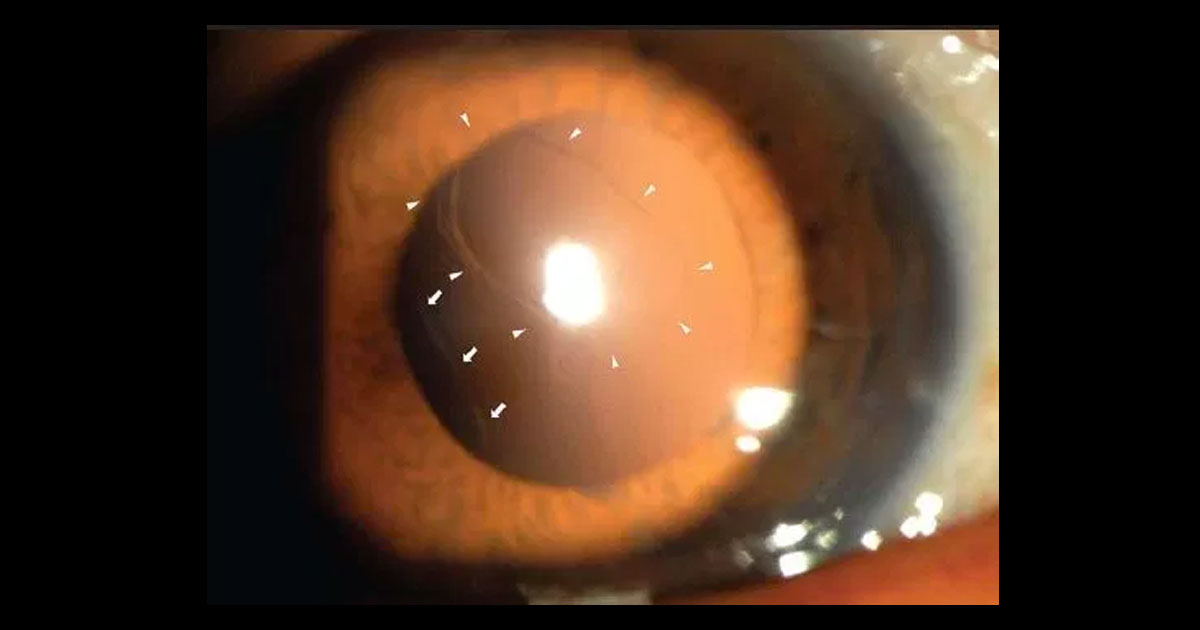

In eyes with vitreous incarcerated in the corneal incision wounds as a result of complicated surgery, YAG laser vitreolysis to break the vitreous strand may be of benefit. Significant vitreomacular traction can be released with vitrectomy.

For cases that fail to respond to topical treatment, the options include periocular steroids, intravitreal anti VEGF agents or intravitreal triamcinolone. Studies have demonstrated that periocular steroid injections (orbital floor or sub-tenons injections) can be beneficial (5). However such treatment does pose the risk of raised intraocular pressure. Early evidence also supports a potential role for intravitreal anti-VEGF agents (6,7), which avoids the risk of raised IOP, but does carry a small risk of endophthalmitis. In my experience, where these treatments have failed to produce an adequate response, the use of intravitreal triamcinolone is indicated (8), as this technique allows the delivery of a maximal dose of steroid to the macula. The higher risk of raised IOP, in conjunction with the risk of endophthalmitis, is why I limit this treatment to the most recalcitrant cases.