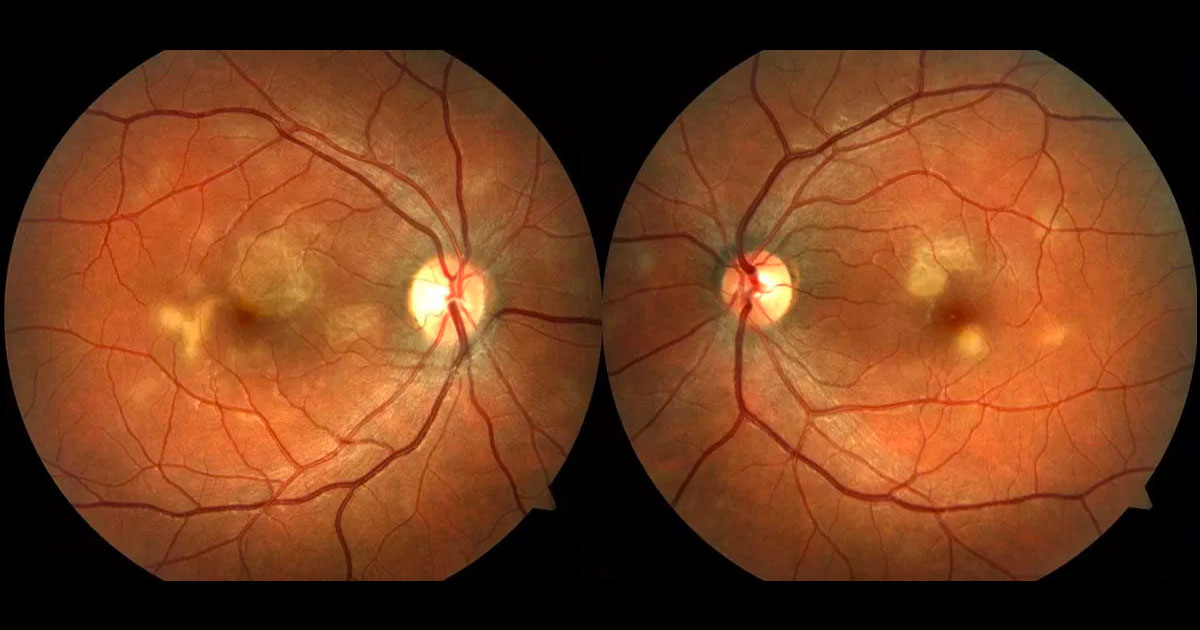

Acute posterior mulitifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) was described by Donald Gass in 1968,(1) and is characterised by a rapid, transient loss of visual acuity associated with an acute onset of multiple, discrete yellow-white placoid lesions at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the posterior pole. At least 75% of cases are bilateral,(2) and males are equally as affected as females. About 1/3 of cases are preceded by a viral illness. Other visual symptoms include paracentral scotomas, metamorphopsia, “spots” in the vision, and photopsies. Typically this condition presents between the ages of 20 and 50 years, with the mean age of onset being 26 years (similar to our patient). Vitritis is not a significant component of APMPPE, but patients can even present with an anterior uveitis, such as in this case. Other inflammatory “white dot” syndromes often present with significant vitritis, such as birdshot chorioretinopathy and multifocal choroiditis with panuveitis, so this can be a useful differentiating factor.

Most patients with APMPPE demonstrate spontaneous improvement over 2-4 weeks. However, 25% of patients still end up with a visual acuity of 6/12 or worse, so the prognosis is not as good as once thought.(2) Most patients who do not achieve a complete recovery have foveal involvement at presentation, so there is a trend to treat these patients with corticosteroids. Those without foveal involvement normally make a good recovery without any treatment. There are no scientific studies proving that steroids are useful to treat APMPPE, but in more severe cases, they should be considered. As with any cause of uveitis, it is important to exclude infections such as syphilis and tuberculsosis, before commencing steroids. It is imperative that APMPPE patients are asked about neurological symptoms such as severe headache, limb weakness, paraesthesias or disturbance, in case a cerebral vasculitis is present. These patients need an urgent cerebral magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and if cerebral vasculitis is present, they urgent ueurological admission for intravenous steroids(3).

Additional ophthalmic investigations certainly assist in making the diagnosis of APMPPE and differenting this from other “white dot” syndromes. Gass(1) described the lesions in early phase fluorescein angiography as non-fluorescent, with obstruction of choroidal fluorescence. Later in the angiogram there is a progressive, irregular staining of the lesions, thus giving the usual finding of “early hypoflourescence and late hyperflourescence”. Indocyanine green angiography (ICG) shows hypoflourescence throughout the entire study, early and late, which gave way to the theory that APMPPE is due to choriocapillaris occlusion. The exact pathogenesis of the disease is still debated today, as Gass believed the primary pathology was at the level of RPE(1). Fundus autofluorescence in acute APMPPE shows the lesions to be hypoautoflourescent in the centre, with some hyperautoflourescence at the lesion borders.(4) During the recovery phase, the hyperautoflourescence areas fade, indicating recovery of the RPE. The OCT changes in the acute setting of the placoid lesions show hyperreflectivity changes in the outer retinal layers with disruption of the phtoreceptors.(5) As the vision recovers, there is a recovery of the photoreceptors, but this is not always complete, which is why some patients with APMPPE are left with some permanent visual disability.